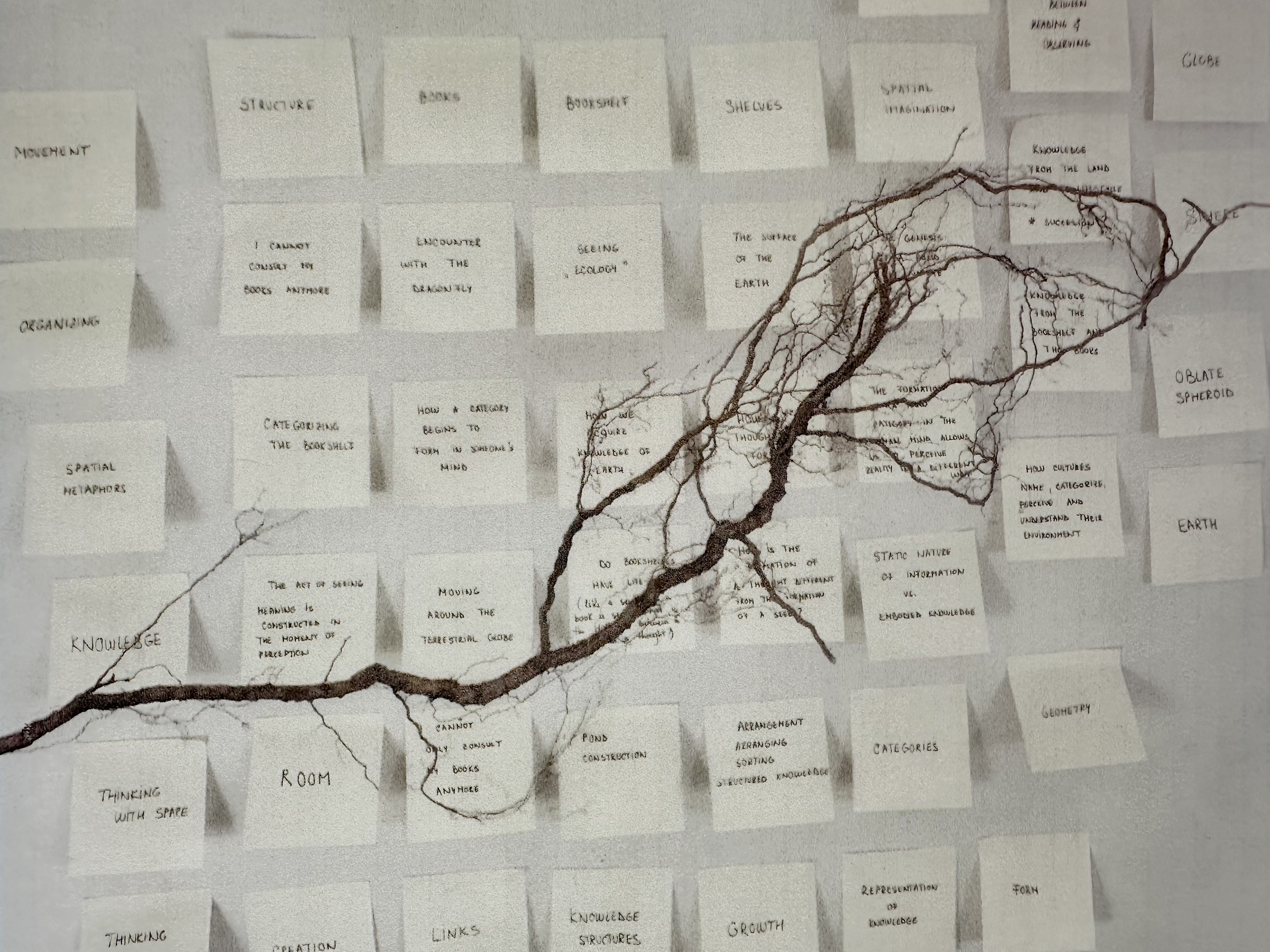

During my time at RISD, I became fascinated with classification systems, categorization, and the different ways we acquire knowledge of Earth. I created a fictional character to map the experience of becoming an ecological thinker, to explore the relationship between perception and the categories through which we perceive, and the tension between static versus dynamic. I chose the mediums of creative writing and photography to tell a story that explored a shift of perception, a transition from one knowledge system to another—from a Western knowledge system to local ecological knowledge.

I wanted to understand the difference between the impetus of seeking knowledge through books, which often is based on scientific theories, data, and analysis, on rationality versus seeking knowledge directly from the land and the land’s life cycles over time - an embodied, tacit knowledge that emerges from subjective experience— from a pre-existing mental model to an understanding that perceives flows, relationships, and interactions. In time, I concluded that both pathways of knowing are important and complement each other. There are endless ways of knowing and being in the world.

I have described it as a character, but what truly is— is a movement, a metamorphosis of a fixed structure, and a way of perceiving the world: a cognitive process of unlearning—questioning fixed, impermeable, homogeneous surfaces, understanding the oscillation between order and disorder, trusting chance encounters, unlearning associations, identifying assumptions guided by the intentionality to give back to the web of life.. But most importantly, I hope it inspires others to think critically about their own relationship with the natural world.

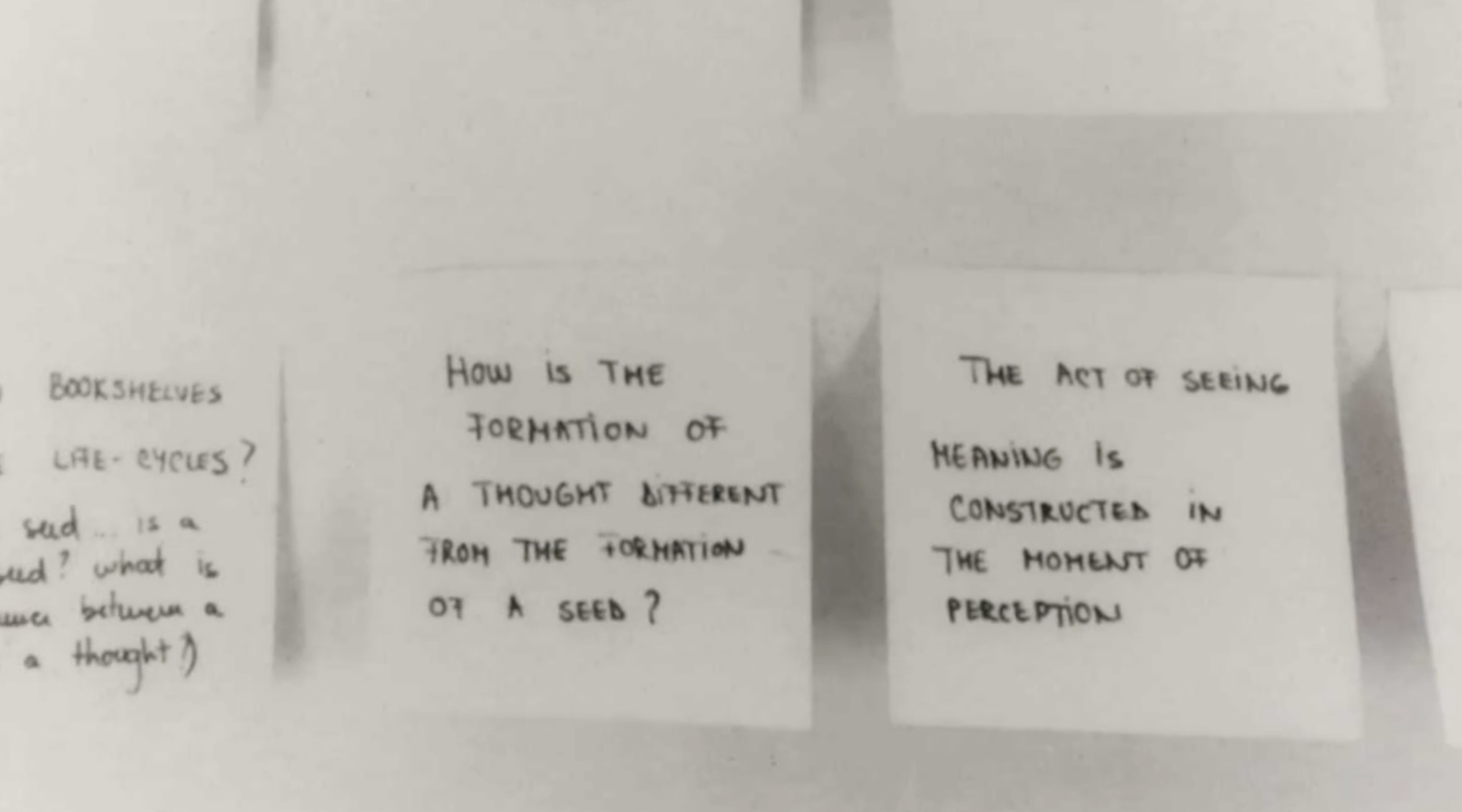

The in-between space is where assumptions are challenged, and new forms of knowledge emerge, leading to transformation. My research approach involves actively seeking, becoming, and tracing knowledge in this in-between space, where categories are not fixed, and meaning emerges as connections are allowed to develop over time. By observing the emergence of meaning and allowing unconscious thoughts to surface, a state of understanding that goes beyond mere knowledge is revealed. For me, knowledge is never fixed, knowing is a continuous movement.

Abstract

A Pond Becomes a Forest questions the terms by which we come to our knowledge systems and asks how we interpret and know nature. This thesis argues for direct encounters with natural forms and the processes that create them. It represents a search to understand ecology through profound attention. It proposes new ways of perceiving and interacting with the natural world.

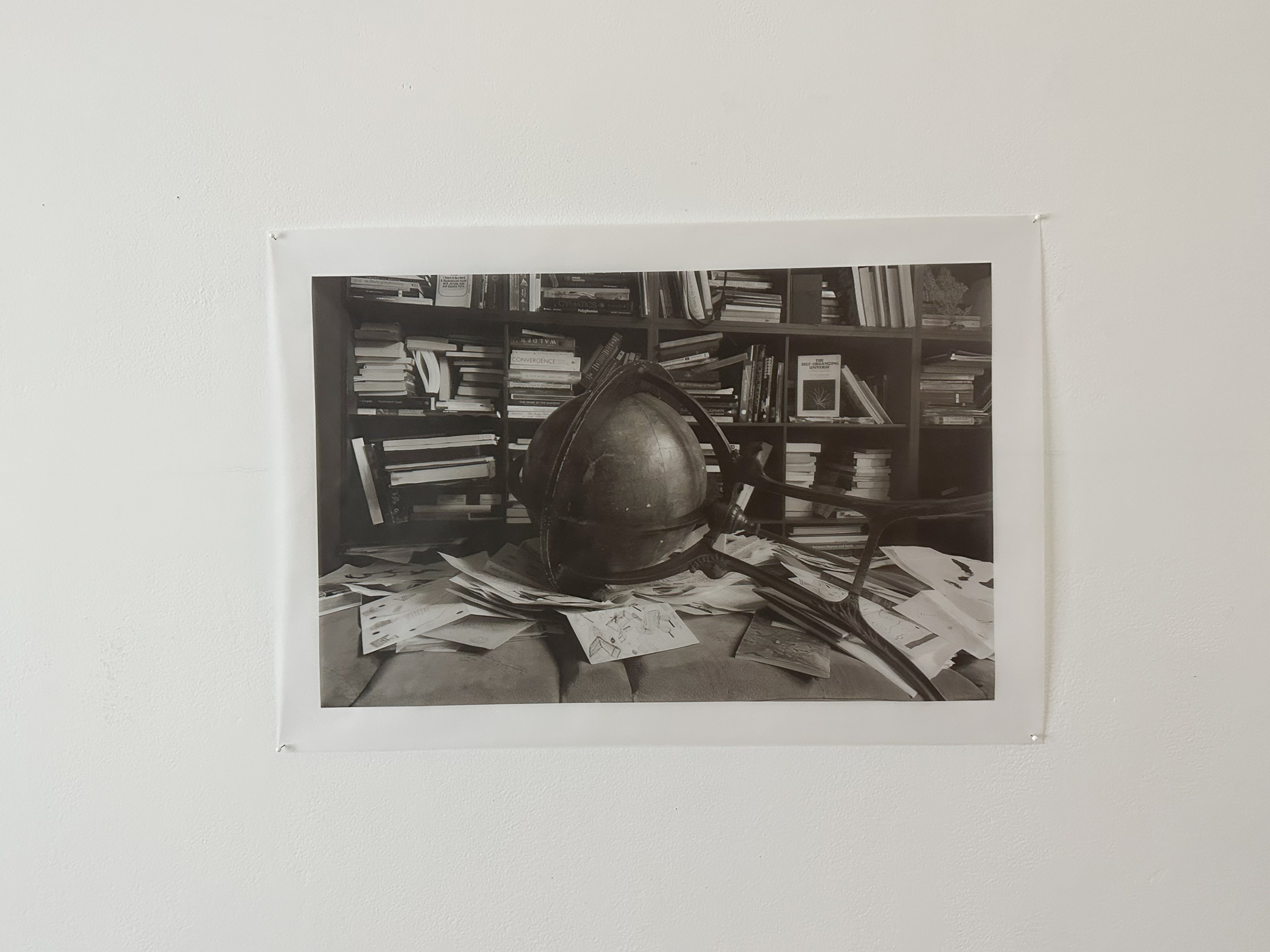

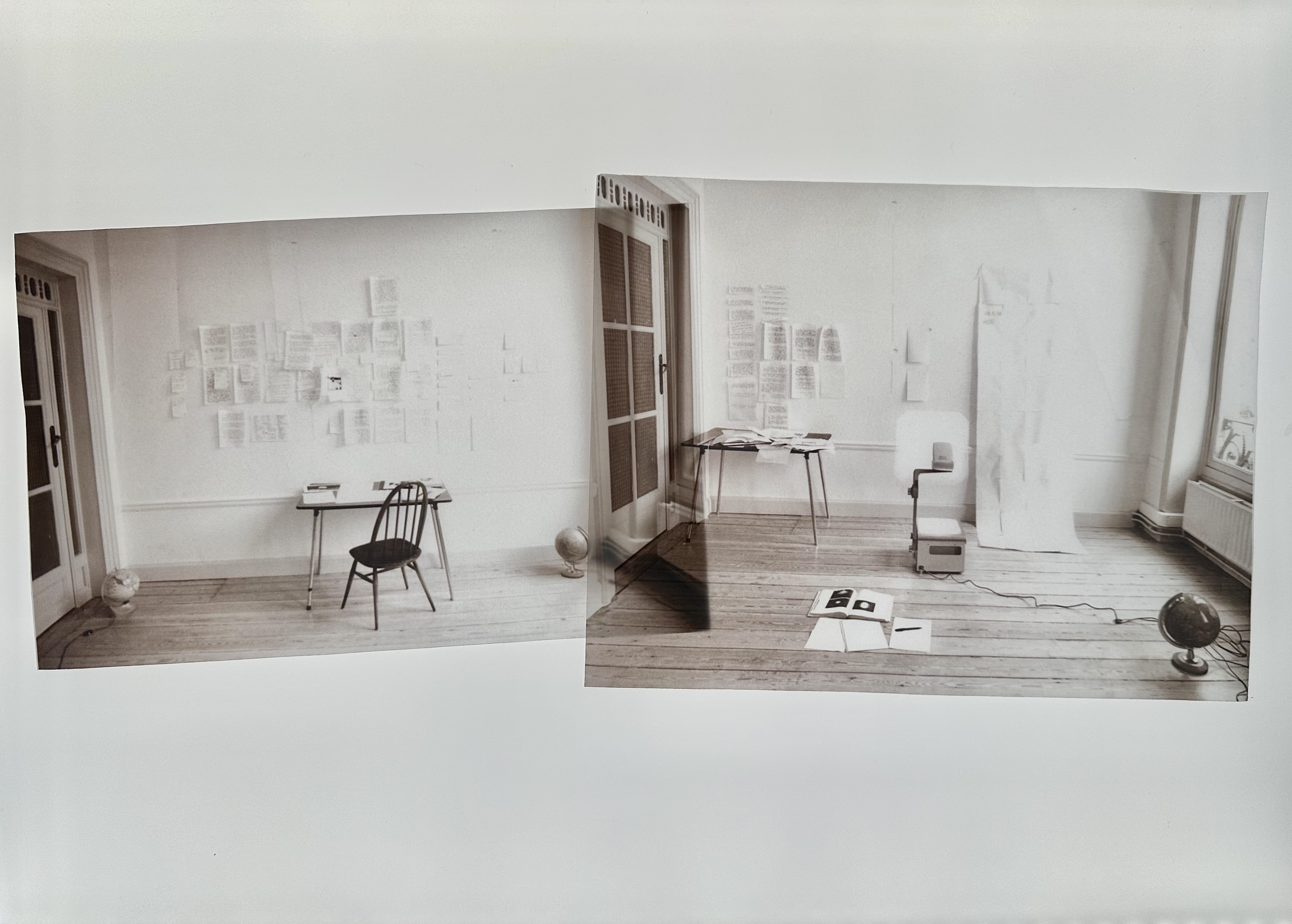

The central character is a bibliophile who discovers a world through books. After years of immersion in words, an imaginary study room emerges, a location that represents her knowledge accumulation. After she directly encounters nature, however, her worldview changes and she transforms into a budding ecologist. As she begins a patient process of observing natural life cycles, a new order of perception unfolds.

Through prose storytelling and empirical research, A Pond Becomes a Forest combines often disjunctive forms of writing as a method of argumentation. Unlike a more static academic paper, this thesis develops non-linearly, blooming outwards across a network of events, associations, meditations, and chance encounters. The writing gathers ideas and approaches to cultivate curiosity, capturing not only how the protagonist tends to her ecological self, but how we all might imagine doing so.

RISD MA in Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies Thesis

Excerpts can be found on the Digital Grad Show website

Video on Vimeo

A Pond Becomes a Forest questions the terms by which we come to our knowledge systems and asks how we interpret and know nature. This thesis argues for direct encounters with natural forms and the processes that create them. It represents a search to understand ecology through profound attention. It proposes new ways of perceiving and interacting with the natural world.

The central character is a bibliophile who discovers a world through books. After years of immersion in words, an imaginary study room emerges, a location that represents her knowledge accumulation. After she directly encounters nature, however, her worldview changes and she transforms into a budding ecologist. As she begins a patient process of observing natural life cycles, a new order of perception unfolds.

Through prose storytelling and empirical research, A Pond Becomes a Forest combines often disjunctive forms of writing as a method of argumentation. Unlike a more static academic paper, this thesis develops non-linearly, blooming outwards across a network of events, associations, meditations, and chance encounters. The writing gathers ideas and approaches to cultivate curiosity, capturing not only how the protagonist tends to her ecological self, but how we all might imagine doing so.

RISD MA in Nature-Culture-Sustainability Studies Thesis

Excerpts can be found on the Digital Grad Show website

Video on Vimeo

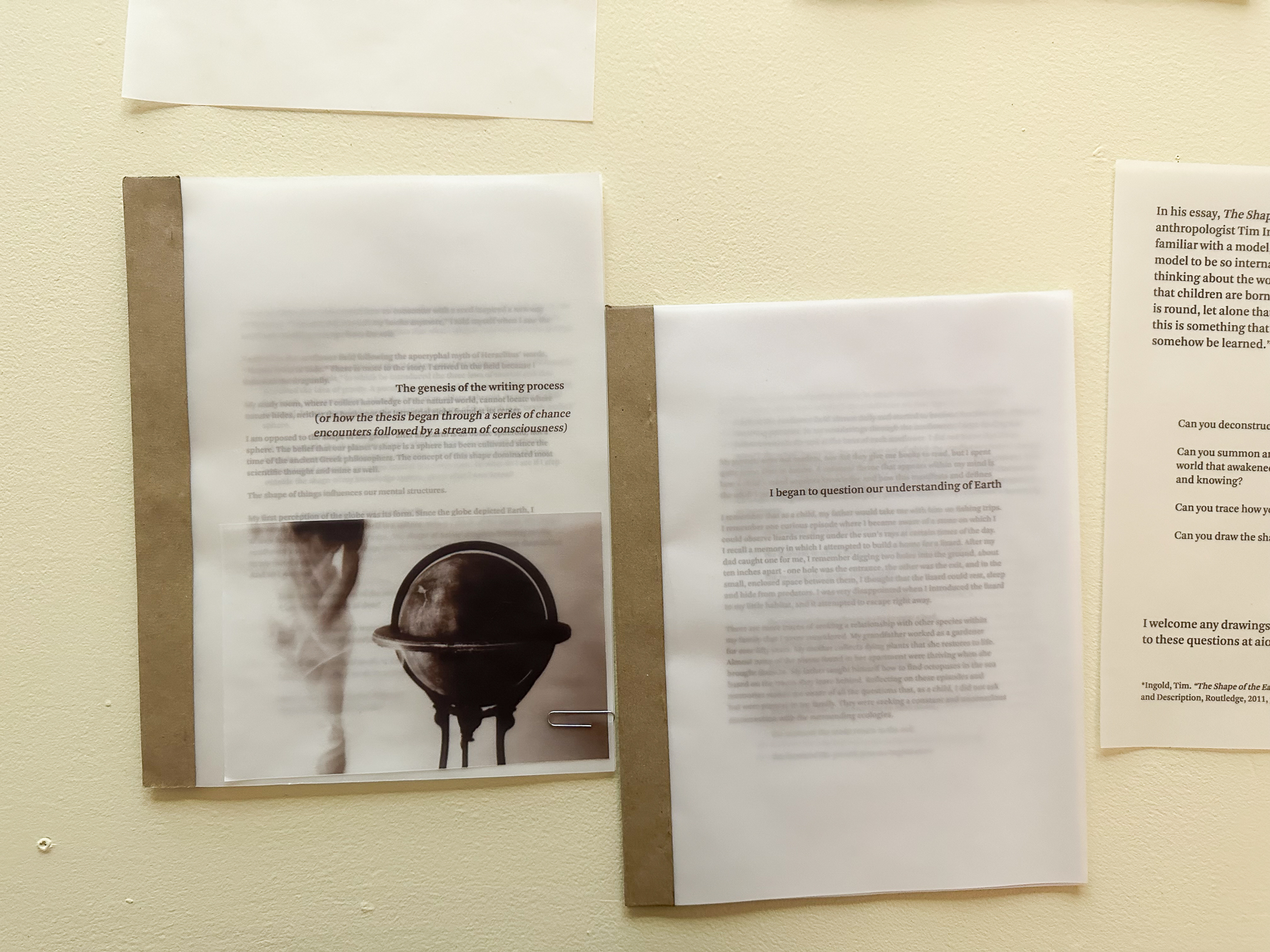

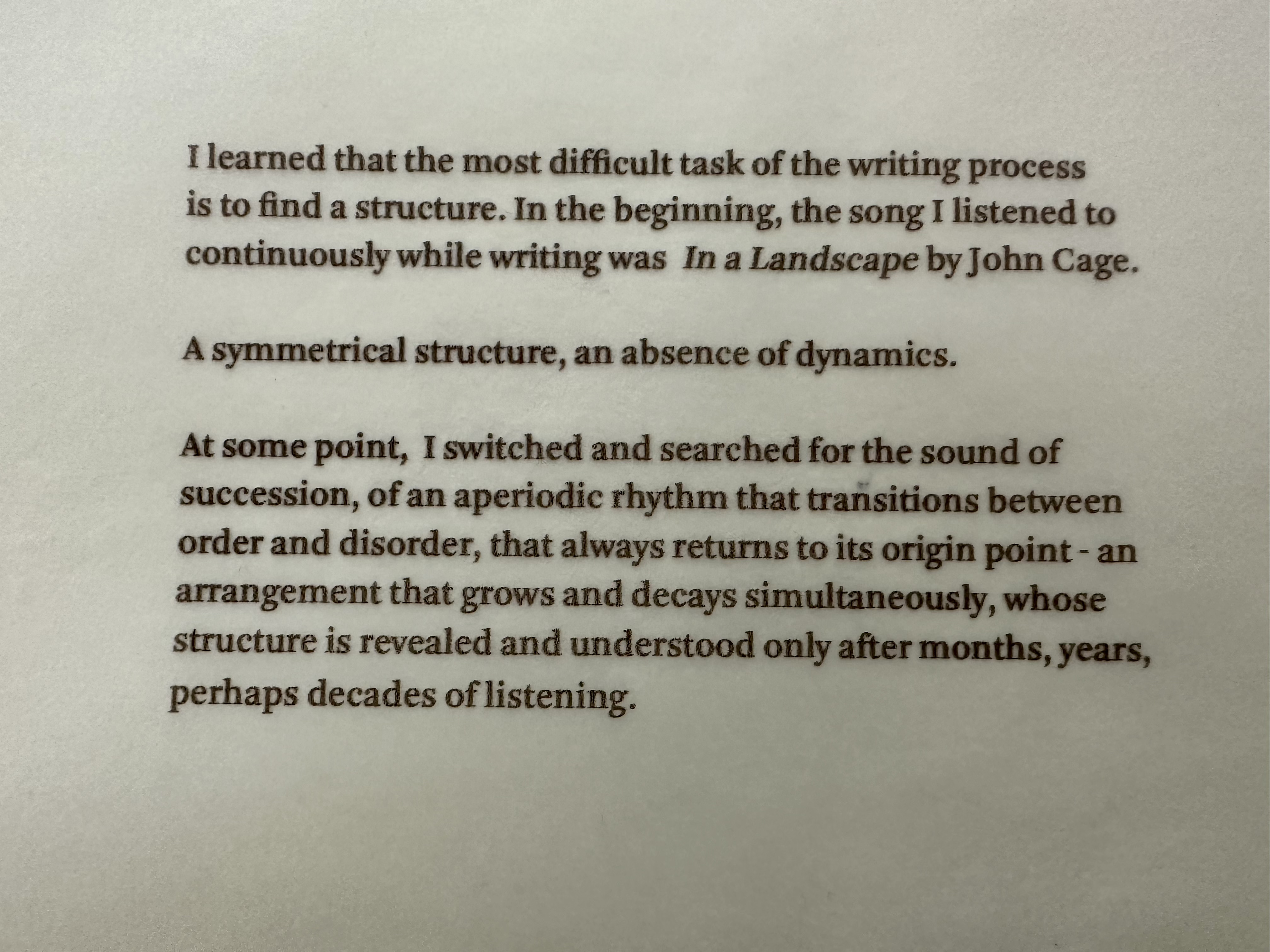

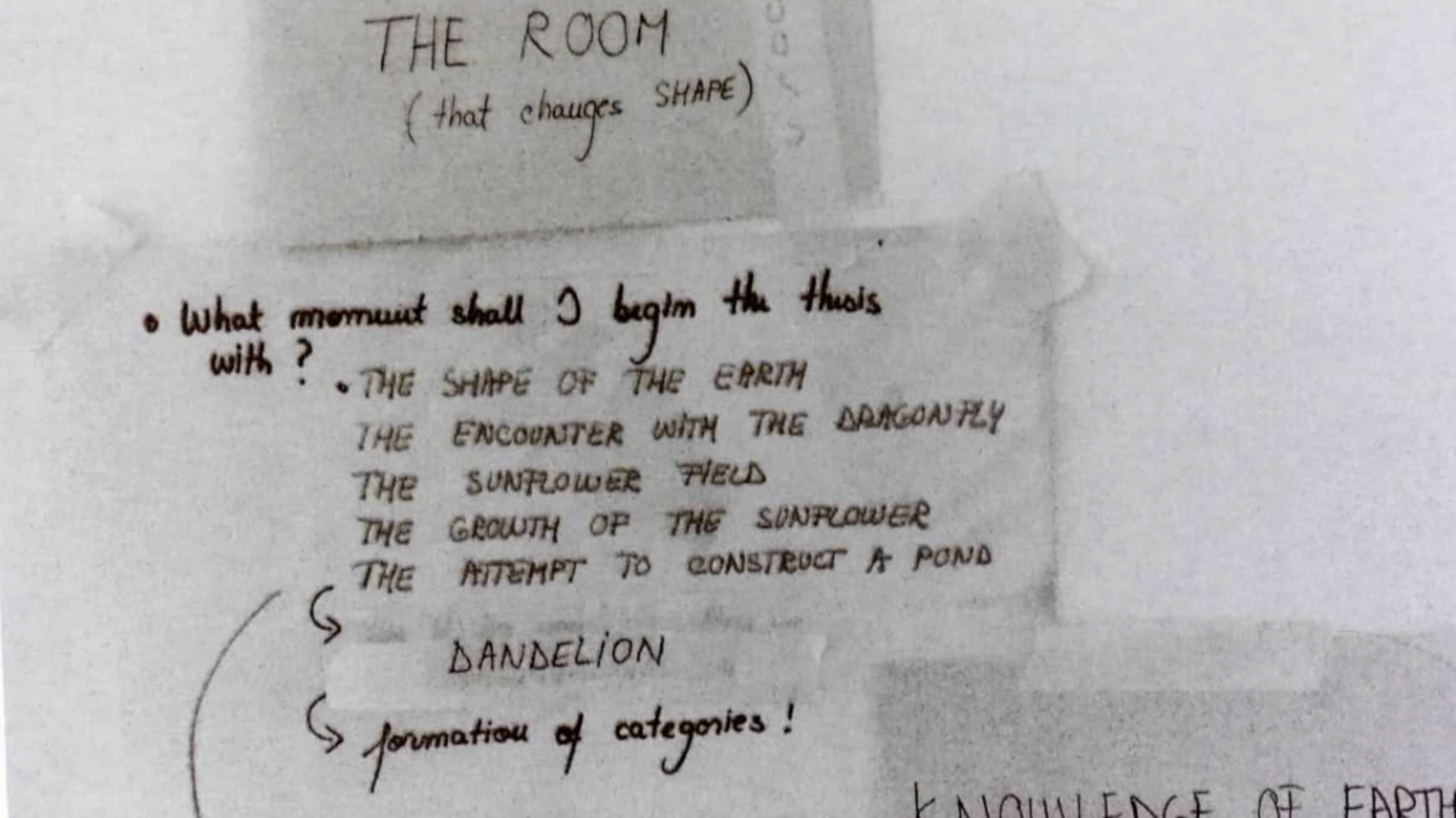

The genesis of the writing process

(or how the thesis began through a series of chance encounters followed by a stream of consciousness)

It may be difficult to understand how an encounter with a seed inspired a new way of thinking. “I cannot consult my books anymore,” I told myself when I saw the sunflower seedling emerge from the soil.

I arrived in the sunflower field following the apocryphal myth of Heraclitus’ words, “Nature loves to hide.” There is more to the story. I arrived in the field because I followed the dragonfly.

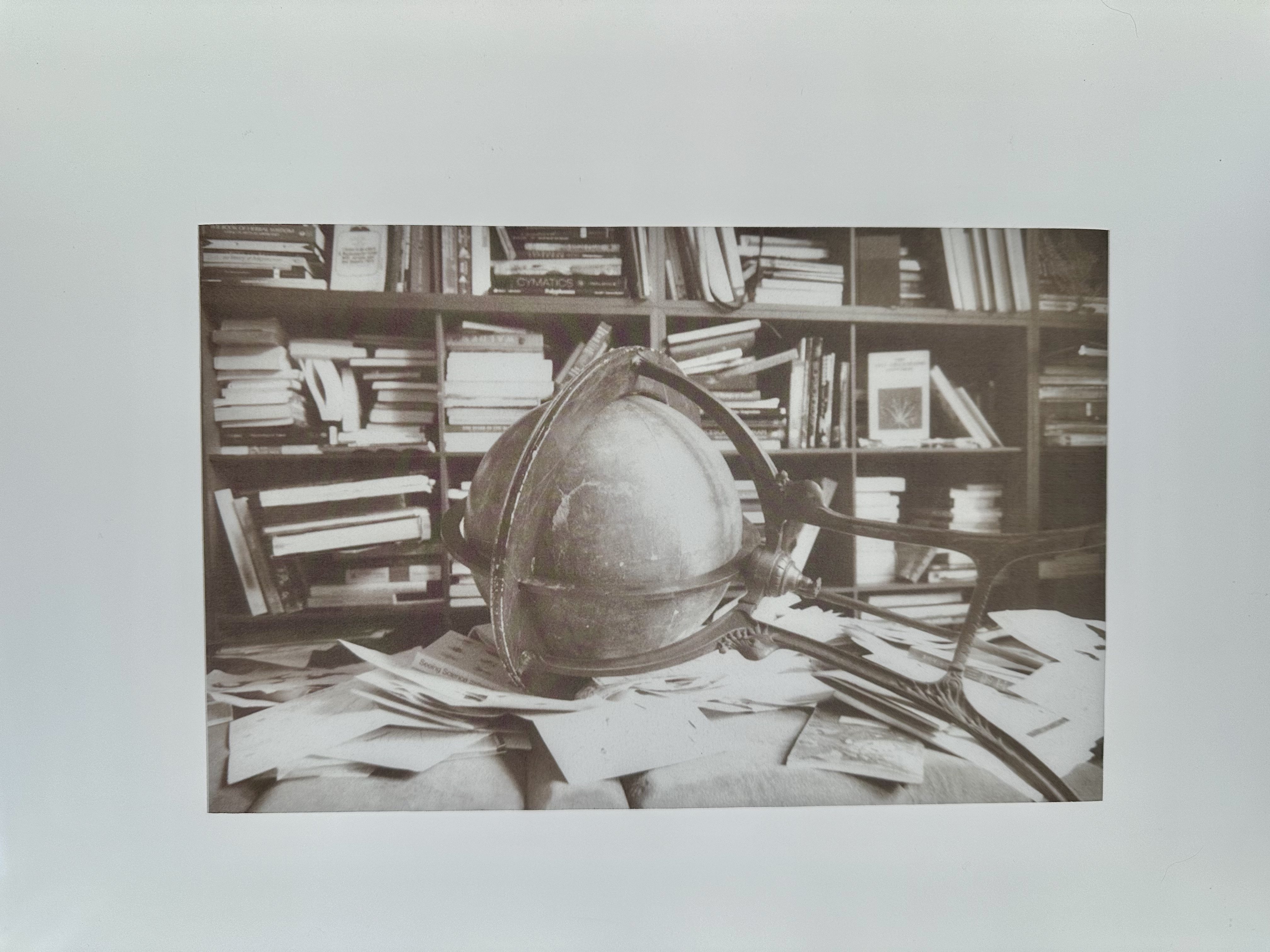

My study room, where I collect knowledge of the natural world, cannot locate where nature hides, neither the books nor the terrestrial globe found at its center.

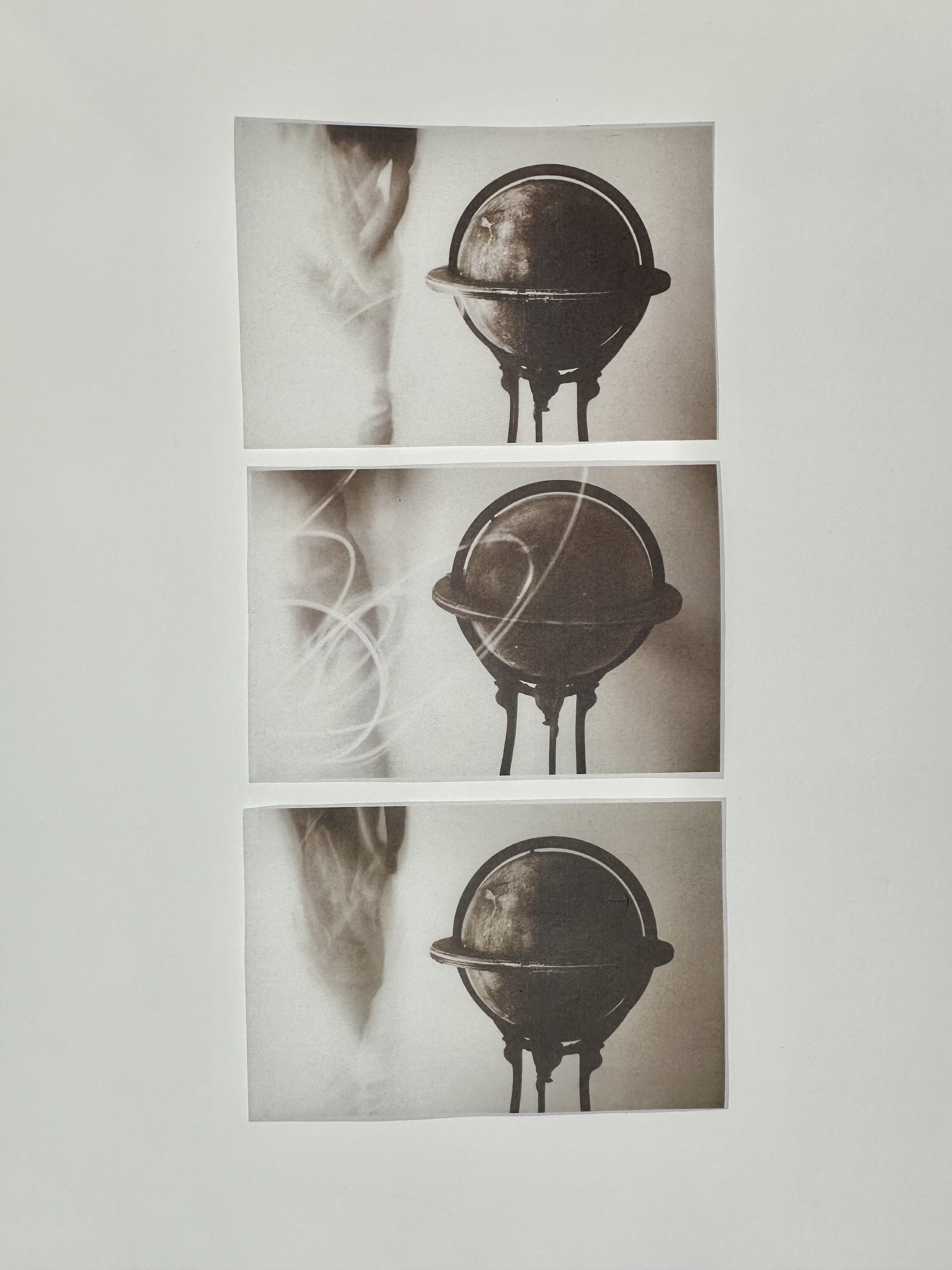

I am opposed to the shape of the globe - after all, Earth is an oblate spheroid, not a sphere. The belief that our planet’s shape is a sphere has been cultivated since the time of the ancient Greek philosophers. The concept of this shape dominated most scientific thought and mine as well.

The shape of things influences our mental structures.

My first perception of the globe was its form. Since the globe depicted Earth, I innocently assumed the Earth itself is a sphere. When I think of the moon, the shape of dew forming on the dragonfly’s eye, the shape of nectar droplets forming on the sunflower’s seed head, or the shape of a dandelion’s clock, spheres reveal themselves in my mind’s eye.

And so I wonder:

The answer is nowhere to be found in my ordered accumulation of knowledge. As my initial assumptions become visible, I want to understand the genesis of my beliefs. And it would be the readers’ assumption that what I wish to understand is the genesis of forms in nature.

In 1678, Isaac Newton published the “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy” known as “Principia,” in which he introduced the three laws of motion and first described the idea of gravity. A peculiar fact he included was a calculation suggesting that Earth, in its revolution, takes the form of an oblate spheroid, its poles slightly flattened. In other words, he predicted that the shape of the Earth is a “nearly perfect” sphere.

If I step outside the shape of the Earth, what I perceive as a smooth surface is irregular, asymmetric—constantly changing. This leads me to believe that my perception of nature in any given instant is a conjecture. So what do I see if I step outside the shape of my knowledge system, given what I now know?

It may be difficult to understand how an encounter with a seed inspired a new way of thinking. “I cannot consult my books anymore,” I told myself when I saw the sunflower seedling emerge from the soil.

I arrived in the sunflower field following the apocryphal myth of Heraclitus’ words, “Nature loves to hide.” There is more to the story. I arrived in the field because I followed the dragonfly.

My study room, where I collect knowledge of the natural world, cannot locate where nature hides, neither the books nor the terrestrial globe found at its center.

I am opposed to the shape of the globe - after all, Earth is an oblate spheroid, not a sphere. The belief that our planet’s shape is a sphere has been cultivated since the time of the ancient Greek philosophers. The concept of this shape dominated most scientific thought and mine as well.

The shape of things influences our mental structures.

My first perception of the globe was its form. Since the globe depicted Earth, I innocently assumed the Earth itself is a sphere. When I think of the moon, the shape of dew forming on the dragonfly’s eye, the shape of nectar droplets forming on the sunflower’s seed head, or the shape of a dandelion’s clock, spheres reveal themselves in my mind’s eye.

And so I wonder:

How is the formation of the moon different from the formation of dew?

How is the shape of a water droplet different from the shape of a nectar droplet?

How is the growth of seeds in a dandelion different from the growth of seeds in a sunflower?

How is the birth of a bee different from the birth of a tornado?

The answer is nowhere to be found in my ordered accumulation of knowledge. As my initial assumptions become visible, I want to understand the genesis of my beliefs. And it would be the readers’ assumption that what I wish to understand is the genesis of forms in nature.

In 1678, Isaac Newton published the “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy” known as “Principia,” in which he introduced the three laws of motion and first described the idea of gravity. A peculiar fact he included was a calculation suggesting that Earth, in its revolution, takes the form of an oblate spheroid, its poles slightly flattened. In other words, he predicted that the shape of the Earth is a “nearly perfect” sphere.

If I step outside the shape of the Earth, what I perceive as a smooth surface is irregular, asymmetric—constantly changing. This leads me to believe that my perception of nature in any given instant is a conjecture. So what do I see if I step outside the shape of my knowledge system, given what I now know?

A terrestrial globe that is not Earth

A dandelion’s life cycle

A sunflower’s growth pattern

A pond becoming a forest

RISD 2023 Grad Biennial

Interior Atlas: Ways of Research

Sol Koffler Graduate Student Gallery @ RISD

co-curated by Anne West and Holly Gaboriault

September 7th - October 12th 2023